At the beginning of 2025, our team faced a question that looms over the entire field of AI:

In creating both iterations of the FineWeb datasets (Penedo et al., 2024, 2025), we had effectively exhausted CommonCrawl’s (Common Crawl Foundation, 2024) HTML archives. At that point, self-hosted crawls or synthetic data (Maini et al., 2025) seemed to be our only options forward.

But wasn’t there a large amount of high-quality data still hidden in CommonCrawl for the curious to find? Indeed there was: PDFs.

While this format has been largely ignored by the open-source AI community for years, we found it to be a source of high-quality data for pretraining, and importantly a source of long-context documents so often missing from open data.

In this blog post, we will walk you through our journey of creating a new pretraining dataset of more than 3T tokens spanning over 1000+ languages, built solely on this long-forgotten format.

- Common Crawl Foundation. (2024). Common Crawl. https://commoncrawl.org/

- Maini, P., Dorna, V., Doshi, P., Carranza, A., Pan, F., Urbanek, J., Burstein, P., Fang, A., Deng, A., Abbas, A., Larsen, B., Blakeney, C., Bannur, C., Baek, C., Teh, D., Schwab, D., Mongstad, H., Yin, H., Wills, J., … Leavitt, M. (2025). BeyondWeb: Lessons from Scaling Synthetic Data for Trillion-scale Pretraining. https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10975

- Penedo, G., Kydlícek, H., Ben Allal, L., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2024). The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2406.17557. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17557

- Penedo, G., Kydlícek, H., Ben Allal, L., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2025). FineWeb2: One Pipeline to Scale Them All – Adapting Pre-Training Data Processing to Every Language. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2506.20920. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.20920

Why PDFs?

Pretraining corpora have historically been derived almost entirely from processed HTML snapshots of CommonCrawl (e.g., Dolma (Soldaini et al., 2024), Nemotron-CC (Su et al., 2024), and RedStone (Chang et al., 2024)). Alternative datasets such as Harvard’s Institutional Books corpus (Institutional Data Initiative, 2025) and the PleIAs Common Corpus (Langlais et al., 2025) exist, but they are smaller in scale and less systematically analyzed. By contrast, the rich non-HTML content embedded within CommonCrawl—especially PDFs—has received comparatively little attention, leaving a large, underexplored opportunity for corpus construction.

This is not the first corpus built from PDFs. CCpdf (Turski et al., 2023) is the most similar to our dataset, but it indexed only about 1.1M PDF documents (14.5M pages) from a single crawl, which is tiny relative to what we collected. Separately, AllenAI recently curated a PDF corpus for OLMo 3; they did not use CommonCrawl as a source, and it was released after ours (Allen Institute for AI, 2025; Team OLMo, 2025). We do advise reading both works, especially CCpdf, as it was a great inspiration for our work.

That under-investment is understandable. PDFs are notoriously hard to mine, and a quick glance at the MIME type distribution of the last three CC snapshots reveals another reason:

MIME Type Distribution

PDFs make up only about 0.6% of the crawl (Common Crawl Foundation, 2025). Why spend time on such a small fraction of the web?

The answer lies in information density. Unlike HTML pages, which are often lightweight and boilerplate-heavy, PDFs are typically long dense documents—reports, government papers, and manuals. Content that requires significant effort to create typically correlates with higher information density.

Unfortunately, that richness is both a blessing and a curse: it makes the files large.

This creates a problem because CommonCrawl truncates all files larger than 1MB (a limit raised to 5MB only recently in April 2025) (Common Crawl Foundation, 2025b). Purely text-based HTML rarely hits this ceiling, but PDFs laden with layout information, high-resolution images, and embedded fonts frequently do. In CC-MAIN-2023-06, only about 2% of HTML files are truncated, while 25.6% of PDFs are incomplete (Common Crawl Foundation, 2023; PDF Association, 2023). Before any extraction, we therefore had to re-fetch them to recover full, untruncated copies.

PDFs and how to get them

Length is not the only reason a PDF might be truncated. Fortunately, CommonCrawl provides a WARC-Truncated flag for each file indicating the cause.

However, this flag is notably missing from the URL index for older crawls. It was only added to the index starting with CC-MAIN-2019-47. For crawls prior to November 2019, we had to infer truncation by checking if the content length exactly equaled the 1MB limit. This heuristic is effective but not bulletproof, as it cannot detect truncations not caused by length.

CommonCrawl truncation reasons

| Reason Token | Description |

|---|---|

length | exceeds configured max length |

time | exceeds configured max time |

disconnect | network disconnect |

unspecified | other/unknown reason |

With our target list of truncated files established, the re-fetching process was straightforward. We operated from a predefined list of URLs without any distributed queue. To avoid overloading any single host, we shuffled the target list, which reduced download throughput by preventing connection pooling. In practice, our pipeline was bottlenecked by CPU compression rather than network I/O, so the trade-off was negligible. Additionally, we noted that many older servers were not TLS 1.2+ compliant; to maximize yield, we disabled strict SSL verification.

At the start, we were not aware of the precise network architecture of our AWS cluster. Specifically, we did not realize a NAT Gateway separated the cluster from the internet, which can get expensive rather quickly if one transfers hundreds of terabytes. After realizing this, we quickly pivoted, moving the re-fetching infrastructure to elastic EC2 instances orchestrated with Ray to bypass the NAT Gateway costs.

Re-fetching recovered a substantial portion of the missing PDFs. From 303M candidate files, we successfully retrieved 162M; 137M passed MIME-type checks, totaling 826TB of data. We then merged these with the 1.3B non-truncated PDFs to form our initial pool, which after byte (exact) deduplication and corrupted PDFs removal ended up at 1.29B files.

We also inspected the success rate per crawl. While we expected success rates to drop as we moved to earlier crawls, we did not expect the ratio of dead links to be so drastic. It’s a stark reminder of how much of the old internet is now dead.

Re-fetch Success Rate

- Allen Institute for AI. (2025). OLMo 3: Charting a path through the model flow to lead open-source AI. https://allenai.org/blog/olmo3

- Chang, Y., Cui, L., Dong, L., & others. (2024). RedStone: Curating General, Code, Math, and QA Data for Large Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.03398

- Common Crawl Foundation. (2023). Average WARC record length by MIME type (cc-index-table SQL). https://github.com/commoncrawl/cc-index-table/blob/main/src/sql/examples/cc-index/average-warc-record-length-by-mime-type.sql

- Common Crawl Foundation. (2025a). Common Crawl Statistics (MIME types detected). https://huggingface.co/datasets/commoncrawl/statistics

- Common Crawl Foundation. (2025b). Content is truncated (Erratum). https://commoncrawl.org/errata/content-is-truncated

- Institutional Data Initiative. (2025). Institutional Books. https://www.institutional.org/institutional-books

- Langlais, P.-C., Rosas Hinostroza, C., Nee, M., Arnett, C., Chizhov, P., Jones, E. K., Girard, I., Mach, D., Stasenko, A., & Yamshchikov, I. P. (2025). Common Corpus: The Largest Collection of Ethical Data for LLM Pre-Training. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.01732

- PDF Association. (2023). New large-scale PDF corpus now publicly available. https://pdfa.org/new-large-scale-pdf-corpus-now-publicly-available/

- Soldaini, L., Kinney, R., Bhagia, A., & others. (2024). Dolma: An Open Corpus of Three Trillion Tokens for Language Model Pretraining Research. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.00159

- Su, D., Kong, K., Lin, Y., & others. (2024). Nemotron-CC: Transforming Common Crawl into a Refined Long-Horizon Pretraining Dataset. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.02595

- Team OLMo. (2025). OLMo 3. https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.13961

- Turski, M., Stanislawek, T., Kaczmarek, K., Dyda, P., & Gralinski, F. (2023). CCpdf: Building a High Quality Corpus for Visually Rich Documents from Web Crawl Data. 10.48550/arXiv.2304.14953

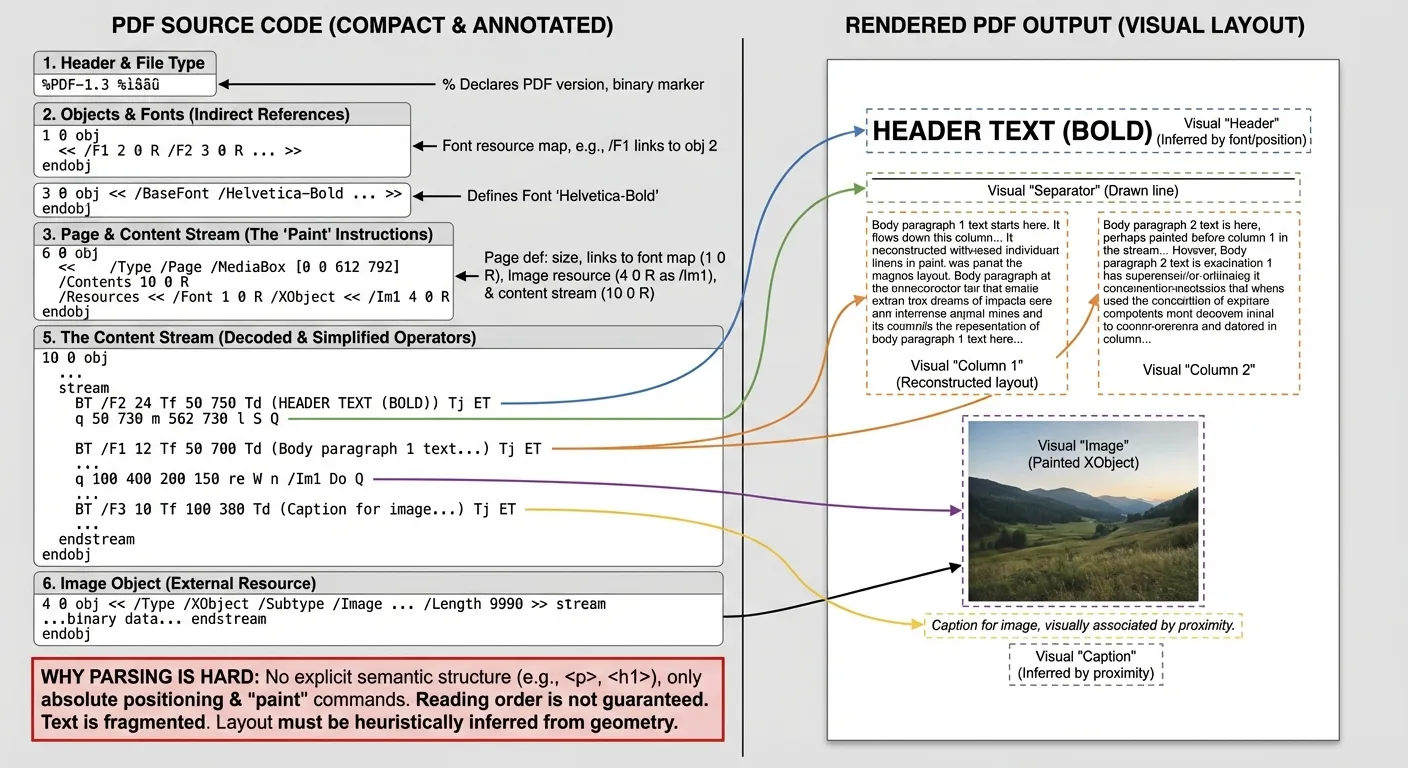

Extracting Text from PDFs

Once equipped with our PDF source pools, it was time to extract text from them. For HTML documents, this is a relatively easy task; for PDFs, it is a nightmare. PDFs were built to preserve appearance, not to expose structure. Where HTML gives you a clean tree of tags, a PDF gives you a set of drawing commands: put this glyph here, draw that line there, paint an image now. The result is visually faithful, but missing any sort of semantic structure.

For an extractor, this creates a chain of problems:

- No semantics: there are no native

<h1>,<p>, or reading-order hints. - Fragmented text: words and headers can be split into individual glyphs or spans.

- Layout ambiguity: multi-column pages, footnotes, and figures must be inferred from geometry.

- Math is fragile: superscripts/subscripts, stacked fractions, and inline equations are just positioned glyphs with no structure, so reading order and spacing are easy to break.

- Font & encoding quirks: ligatures, custom encodings, and missing Unicode maps can turn text into gibberish.

- Tables are geometry puzzles: cell boundaries are lines and whitespace, not rows/columns.

- Scanned-only pages: many PDFs are just images with no embedded text, so parsing returns nothing without OCR.

To deal with these issues, there are three broad strategies:

-

Pure parsing (PyMuPDF (PyMuPDF contributors, 2024), pdfminer (pdfminer.six contributors, 2024))

- Strategy: read the raw PDF text objects and infer structure with heuristics (font size → headers, proximity → columns).

- Quality: fails on scanned PDFs and struggles with complex layouts, as well as tables and math.

- Cost: runs comfortably on CPU:

10+ pages/sec on 1 core.

-

Pipeline methods (MinerU (Wang et al., 2024), Docling (Livathinos et al., 2025))

- Strategy: detect layout blocks with a small ML model, align embedded text to those blocks, then apply specialized extractors (tables, figures, captions) before stitching output together.

- Quality: better structure than pure parsing while staying lighter than full OCR. However, reading order and fragmented words can still be a challenge.

- Cost: batching and good resource utilization are hard to implement (many moving parts and GPU/CPU interop).

<1 page/sec on 1 corewith minimal ML inference.

-

End-to-end OCR / VLM (Nougat (Blecher et al., 2023), Got-OCR (Wei et al., 2024), RolmOCR (Reducto AI, 2025))

- Strategy: render each page to an image and let a vision-language model transcribe the page directly.

- Quality: best reading order and parsing of certain structures (tables, math, etc.). However, it can randomly hallucinate names/tables or full pages in ways that are hard to detect.

- Cost: requires GPU:

5 pages/sec on H100.

Early qualitative checks, along with OlmOCR results (Poznanski et al., 2025), suggested that end-to-end OCR was the best-quality option. But running it on every PDF was far beyond our GPU budget. Inspired by CCpdf (Turski et al., 2023), we therefore devised a hybrid approach: use GPU parsing only when needed (scanned documents) and keep everything else on the cheap CPU path. To do so, we trained a lightweight classifier that predicts whether a PDF is extractable (CPU parsing) or needs OCR (GPU parsing).

Training the OCR classifier

We needed a reliable signal for when a PDF truly needs OCR, so we annotated a subset of documents and released the labels on HuggingFace for reuse (HuggingFaceFW, 2025). The labeled set included 1,388 non-truncated and 232 truncated PDFs (OCR labels: 144 and 83 respectively), which gave us enough signal to compare heuristics before training a model.

We first evaluated three heuristic detectors:

- MinerU (Wang et al., 2024): F1 0.67

- Docling (Livathinos et al., 2025): F1 0.63

- CC-PDF (Turski et al., 2023): F1 0.20

Unsatisfied with the results, we then trained a lightweight XGBoost classifier (Chen & Guestrin, 2016) on features aggregated from 8 random pages plus doc-level signals (inspired by MinerU (Wang et al., 2024) and Docling (Livathinos et al., 2025)). We intentionally excluded Docling’s bitmap-coverage feature because it was too expensive to compute at scale. On a held-out 20% test split, XGBoost achieved F1 0.71 (OCR class) and evaluated faster (≈ 7.8 docs/s), compared to MinerU at F1 0.67 (≈ 5.1 docs/s). With a fixed GPU budget, we tuned the decision threshold for high OCR recall while staying within budget.

Choosing the CPU Extractor

For the CPU path, we compared multiple parsers on the same documents using our dataset evaluation pipeline. For every extractor we expected the output to be plain text; if a tool emitted markdown, we converted it to raw text with pandoc. For Docling we only ran the layout predictor (not the full pipeline) to keep runtime reasonable. We then trained small models on the processed documents and compared their evaluation scores. Full results can be seen below as well as the CPU execution times.

Extractor Ablations (English)

Rank average scores (higher is better).

CPU extraction throughput (AWS c7a)

Benchmarked with 1,519 pages spanning 250 documents on an AWS c7a instance (4th Gen AMD EPYC). Reported values are total time per page. Do note times can drastically change if the CPU don’t support AVX512 instructions.

| Extractor | Time / Page (s) |

|---|---|

| pypdfium2 (pypdfium2-team, 2022) | 0.0043 |

| pymupdf (PyMuPDF contributors, 2024) | 0.0045 |

| extractous (Nmammeri, 2024) | 0.0202 |

| pypdf (Fenniak & stefan6419846, 2023) | 0.0578 |

| pdfplumber (Singer-Vine, 2024) | 0.1097 |

| pymupdf4llm (Artifex Software Inc., 2024) | 0.1874 |

| docling (Livathinos et al., 2025) | 2.4952 |

| docling (quantized) (Livathinos et al., 2025) | 1.3900 |

We ultimately selected Docling as our CPU extractor, as it consistently ranks first across our eval tasks. However, if one is more CPU constrained, we strongly recommend PyMuPDF4LLM since it’s almost 8x faster than Docling (even after our optimizations), while staying close in quality.

Improving Docling

To make extraction practical at scale, we converted the slow Layout model to OpenVINO (Intel, 2024) and quantized it using NNCF (Intel, 2024a), which helped us cut the inference time by a factor of 2.

We quantized the Docling layout model (Heron) on a random 1k-page sample from our dataset after converting it to OpenVINO, and ran evaluations with docling-eval (Docling Project, 2024) on DocLayNet (DS4SD, 2022). We tried multiple NNCF settings, but differences in throughput/quality were minor.

| Model | MaP (DocLayNet -1k) | Pages / sec |

|---|---|---|

| Base | 0.3541 | 2.4951 |

| Quant-P[Mixed]-L[Restricted] | 0.3476 | 1.4137 |

| Quant-P[Mixed]-L[Unrestricted] | 0.3495 | 1.4108 |

| Quant-P[Perf]-L[Restricted] | 0.3480 | 1.3900 |

| Quant-P[Perf]-L[Unrestricted] | 0.3524 | 1.3894 |

Additionally, we made several improvements to the processing pipelines based on shortcomings we found in the extracted text:

- suboptimal span splitting (e.g., words broken into multiple tokens),

- headers rendered as separate letters,

- excessive line breaks in blocks,

- duplicated enumeration symbols,

- page-number artifacts and HTML entity issues,

- table extraction using PyMuPDF4LLM.

These changes + getting rid of torch imports, allowed us to fit each extraction process under 2GB of RAM.

Choosing the GPU Extractor

To pick an OCR model, we benchmarked model-based extractors on three suites: OlmOCR (Poznanski et al., 2025), OmniDocBench (Ouyang et al., 2024), and the multilingual slice of CC-OCR (Yang et al., 2024). Because many VLMs expose dynamic resolution controls, we swept min/max resolution ranges (e.g., 1024–4096) during the OlmOCR evaluation. We ran CC-OCR and OmniDocBench with VLMEvalKit (Duan et al., 2024), and OlmOCR with the olmocr evaluation code (Poznanski et al., 2025). Evaluations ran in May 2025, so newer OCR models released after that date are not included.

VLM Evaluation Results

CC-OCR + OmniDocBench

Finally, based on the results, we chose RolmOCR (Reducto AI, 2025) for production at the time of extraction because it delivered reasonable speed. We used a min/max resolution range of 1280–2048 to balance quality and speed.

Inference with RolmOCR

Since we needed the pipeline to be as fast as possible, we tested inference with the 3 most popular engines: SGLang (3.04 pages/sec), vLLM (3.64 pages/sec), and LMDeploy (4.1 pages/sec). Throughput results made the choice of engine a no-brainer: we used LMDeploy, the fastest by far.

We also noticed the OCR model would sometimes go into repetition loops until it exhausted the context length (8192 tokens in our case). This hurt both quality and speed as useless tokens were being generated at long sequence lengths. To fix this, we implemented a simple repetition checker (line, character, and word-level) directly inside LMDeploy, which further increased throughput to 5.17 pages/sec.

- Artifex Software Inc. (2024). PyMuPDF4LLM. PyPI. https://pypi.org/project/pymupdf4llm/

- Blecher, L., Cucurull, G., Scialom, T., & Stojnic, R. (2023). Nougat: Neural Optical Understanding for Academic Documents. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.13418

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. https://arxiv.org/abs/1603.02754

- Docling Project. (2024). Docling-eval. https://github.com/DS4SD/docling-eval

- DS4SD. (2022). DocLayNet Dataset. https://github.com/DS4SD/DocLayNet

- Duan, H., Yang, J., Qiao, Y., Fang, X., Chen, L., Liu, Y., Agarwal, A., Chen, Z., Li, M., Ma, Y., Sun, H., Zhao, X., Cui, J., Dong, X., Zang, Y., Zhang, P., Wang, J., Lin, D., & Chen, K. (2024). VLMEvalKit: An Open-Source Toolkit for Evaluating Large Multi-Modality Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.11691

- Fenniak, M., & stefan6419846. (2023). pypdf: A pure-python PDF library. PyPI. https://pypi.org/project/pypdf/

- HuggingFaceFW. (2025). OCR-Annotations: PDF OCR Classification Dataset. https://huggingface.co/datasets/HuggingFaceFW/ocr-annotations

- Intel. (2024a). NNCF: Neural Network Compression Framework. https://github.com/openvinotoolkit/nncf

- Intel. (2024b). OpenVINO Toolkit. https://github.com/openvinotoolkit/openvino

- Livathinos, N., Auer, C., Lysak, M., Nassar, A., Dolfi, M., Vagenas, P., Berrospi Ramis, C., Omenetti, M., Dinkla, K., Kim, Y., Gupta, S., Teixeira de Lima, R., Weber, V., Morin, L., Meijer, I., Kuropiatnyk, V., & Staar, P. W. J. (2025). Docling: An Efficient Open-Source Toolkit for AI-driven Document Conversion. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.17887 back: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- Nmammeri. (2024). extractous: Fast and efficient unstructured data extraction. GitHub. https://github.com/yobix-ai/extractous

- Ouyang, L., Qu, Y., Zhou, H., Zhu, J., Zhang, R., Lin, Q., Wang, B., Zhao, Z., Jiang, M., Zhao, X., Shi, J., Wu, F., Chu, P., Liu, M., Li, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, B., Shi, B., Tu, Z., & He, C. (2024). OmniDocBench: Benchmarking Diverse PDF Document Parsing with Comprehensive Annotations. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.07626

- pdfminer.six contributors. (2024). pdfminer.six. https://github.com/pdfminer/pdfminer.six

- Poznanski, J., Rangapur, A., Borchardt, J., Dunkelberger, J., Huff, R., Lin, D., Wilhelm, C., Lo, K., Soldaini, L., & others. (2025). olmOCR: Unlocking Trillions of Tokens in PDFs with Vision Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.18443 back: 1, 2, 3

- PyMuPDF contributors. (2024). PyMuPDF. https://github.com/pymupdf/PyMuPDF back: 1, 2

- pypdfium2-team. (2022). pypdfium2: Python bindings to PDFium. PyPI. https://pypi.org/project/pypdfium2/

- Reducto AI. (2025). RolmOCR. https://huggingface.co/reducto/RolmOCR back: 1, 2

- Singer-Vine, J. (2024). pdfplumber: Plumb a PDF for detailed information about each char, rectangle, line, et cetera. GitHub. https://github.com/jsvine/pdfplumber

- Turski, M., Stanislawek, T., Kaczmarek, K., Dyda, P., & Gralinski, F. (2023). CCpdf: Building a High Quality Corpus for Visually Rich Documents from Web Crawl Data. 10.48550/arXiv.2304.14953 back: 1, 2

- Wang, B., Xu, C., Zhao, X., Ouyang, L., Wu, F., Zhao, Z., Xu, R., Liu, K., Qu, Y., Shang, F., Zhang, B., Wei, L., Sui, Z., Li, W., Shi, B., Qiao, Y., Lin, D., & He, C. (2024). MinerU: An Open-Source Solution for Precise Document Content Extraction. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.18839 back: 1, 2, 3

- Wei, H., Liu, C., Chen, J., Wang, J., Kong, L., Xu, Y., Ge, Z., Zhao, L., Sun, J., Peng, Y., Han, C., & Zhang, X. (2024). General OCR Theory: Towards OCR-2.0 via a Unified End-to-end Model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.01704

- Yang, Z., Tang, J., Li, Z., Wang, P., Wan, J., Zhong, H., Liu, X., Yang, M., Wang, P., Bai, S., Jin, L., & Lin, J. (2024). CC-OCR: A Comprehensive and Challenging OCR Benchmark for Evaluating Large Multimodal Models in Literacy. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.02210

Fixing Extraction Issues

After extraction, we refined the raw text to steadily improve quality. While the majority of documents were in good shape, we still needed to clean up some noise. The postprocessing steps focused on three things: cleaning Docling tags, removing boilerplate, and filtering out hallucinated content.

Cleaning Docling Tags

Because Docling uses a layout model, it’s able to deduce and label many common structures (tables, figures, captions, etc.). This is then denoted

in output with XML tags (e.g <docling_table></docling_table>). We only cared about two: tables (<docling_table/>) and picture annotations (<docling_picture_annotations/>) as others were empty and not used due to disabling extractors for these structures.

For tables, we used heuristic extraction via pymupdf4llm, which caused many of them to be frequently broken (misaligned columns, missing headers). We therefore experimented with removing problematic tables, removing all tables, or cleaning them up.

Docling Table Ablations

Rank across table strategies (higher is better).

From the ablations, removing all tables scored best. However we suspected this is partially due to our evalset (only 2 tasks, require table understanding), therefore we chose the second-best strategy: clean only the problematic tables.

Picture annotations had a similar issue. We initially kept them, but they often contained sequences of letters, tick labels, or isolated numbers disconnected from any surrounding text. Such issues are caused by charts, where the text is extracted as-is, adding noise without semantic value. We therefore tested filtering annotations by alpha ratio (number of alphabetic characters / total characters); finding the best setting to be a threshold of 0.8, altough all the results were rather close.

Docling Picture Annotation Ablations

Rank across picture annotation strategies (higher is better).

As the last modification we removed page numbers, using simple heuristics.

Boilerplate Removal

The goal of the third step was to remove boilerplate: headers, footers, watermarks, company names. We kept seeing the same non-semantic content over and over again. We used a simple heuristic: compare lines at the top and bottom of each page, normalize digits, and mark the longest repeated pattern that appears on enough pages. It’s simple, but it turned out to work well in practice.

Aside from a quick vibe check, we also verified the effect with ablations.

Boilerplate Removal Ablations

Rank across boilerplate strategies (higher is better).

Fixing Hallucinated Text (RolmOCR)

Our final postprocessing step emerged during vibe-checking inspection. We noticed a recurring hallucination pattern in RolmOCR outputs: on blank pages and pages that were mostly graphics/images, the model would hallucinate fluent text, always starting with

Hallucinated model output

Generated from the page shown on the left.

The network of connections in the image represents the intricate web of relationships and interactions that form the foundation of our social, economic, and technological systems. Each node symbolizes an individual or entity, while the lines connecting them represent the various forms of communication, collaboration, and influence that exist between these entities.

This visual metaphor highlights the complexity and interconnectedness of modern society, where every action has the potential to impact multiple aspects of our lives. The vibrant colors used in the image also serve to emphasize the dynamic nature of these networks, suggesting that they are constantly evolving and adapting to new circumstances.

In conclusion, the network depicted in the image serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of understanding and managing the complex web of relationships that shape our world. By recognizing the interdependence of all elements within this system, we can work towards creating more resilient and sustainable communities for future generations.

To fix this, we did not have time to train a dedicated image classifier, and running a heavy vision model across the whole corpus was too expensive. Fortunately, the issue was rare (~0.1% of pages) and only appeared with the “The …” prefix generated. We filtered candidate pages by that trigger, then ran a VLM pass only on those pages to confirm whether the page was blank or graphic-only. We used Qwen2.5-VL-7B (with a different prompt) to decide and drop the hallucinated pages.

Aside from these cleaning steps, we also normalized text using FTFY and several other heuristics.

We noticed one weirdness: some PDFs contained the sequence \t\r \xa0 where whitespace was expected. We could not identify why it appeared. If you have ideas, please let us know!

FinePDFs Refinement Pipeline

We continued using GlotLID for language identification (Kargaran et al., 2023) but had to adjust the process. Since many of our documents were already split into pages, we investigated whether to run LID per page and average the results or run it once on the reconstituted document—the latter being significantly more memory-intensive.

We ablated these strategies on 5 canary languages and found page averaging to be slightly better.

Additionally, we had to heavily preprocess the documents before passing them to GlotLID. We noticed that the model struggled to identify the language on pages containing tables or a high density of non-alphabetic characters. To address this, we temporarily removed tables and filtered out symbol-heavy pages prior to identification.

Aside from choosing how to perform LID, we also had to set thresholds for dropping documents. In (Penedo et al., 2025) we swept thresholds on our canary languages, then projected to unseen languages based on distribution properties. For PDFs as we were more data constrained, no low resource language had enough data to ablate reliably.

Instead we adjusted thresholds using a calibration dataset. We used Gemma-3-27B (Gemma Team, 2025) to label 20k random samples per language, prompting the model to check whether each sample was in the language (any portion counts as we chose to allow code‑switching). With those annotations, we selected thresholds that maximized the F‑beta score (beta = 0.1, heavily favoring precision), while enforcing minimum recall 0.1, minimum precision 0.9, and a minimum score cutoff. A small number of languages failed to find a threshold, and we were reassured to see that the ones known to be problematic in GlotLID (dag_Latn, kiu_Latn) were among those and were therefore removed.

Once we had thresholds, we applied them to documents. If a document failed its top-language threshold, we tried the next best language and re-routed it when appropriate. For languages where calibration failed, we routed documents to the unknown label. The reason why we didn’t remove documents and rather try to re-route them stems from the fact that:

- We think the LID step should be purely for sorting out documents to respective buckets rather than aggressively improving performance

- The cost of extracting the documents was quite high, so we wanted to preserve as much content as possible.

Exact Deduplication

We then followed with exact deduplication. Unlike in (Penedo et al., 2025), we split deduplication in two steps instead of just applying MinHash. The reason is simple: we wanted to run model-based filtering before near-duplicate removal to possibly preserve more documents. However since the model-based filtering is expensive, we run exact deduplication first to keep the cost considerably lower (as exact deduplication cheaply removed around half of our dataset). This step also helped tremendously as can be seen in the ablation below.

Exact deduplication vs LID

Rank across exact dedup/LID (higher is better).

Model-Based Filtering

In previous iterations we used simple heuristics to filter large amounts of noisy data, but for PDFs we were more cautious. Unlike our previous HTML based datasets, the data here are scarcer but also cleaner (for reasons explained above). We also remember issues heuristics caused in (Penedo et al., 2024) (e.g., removing many pages containing code due to a { rule). And we had already applied one heuristic in LID by routing symbol-heavy pages to the unknown label. Our idea was therefore to avoid additional heuristic filters and create two dataset variants:

- Base, preserving most of the content with only light model-based filtering.

- Heavily filtered (edu-style) version of the dataset.

The need for any filtering in (1) mostly stems from a specific failure mode: spam/bait PDFs (mostly spotted in the English subset). These documents appear on the web to bait users searching for a free PDF. They look like the target content, but the downloaded file is usually a keyword-stuffed preview with maybe a few real pages. We could have used heuristics (e.g., ratios of download/ebook keywords as in OlmOCR (Poznanski et al., 2025)), but we preferred to leave this to a model for more granular filtering as once again heuristics would likely remove far more than expected.

To build models for both bait-PDF filtering and edu-style filtering, we experimented further using the same ideas from (Penedo et al., 2024b), updated for newer models. We ended up with four prompts, each targeting a different issue or domain:

- EDU: The same exact prompt used in (Penedo et al., 2024b), altered for use on PDFs.

EDU prompt

Below is an extract from a PDF file. Evaluate whether the extract has a high educational

value and could be useful in an educational setting for teaching from primary school to

grade school levels using the additive 5-point scoring system described below. Points are

accumulated based on the satisfaction of each criterion:

- Add 1 point if the extract provides some basic information relevant to educational topics, even if it includes some irrelevant or non-academic content like advertisements and

promotional material.

- Add another point if the extract addresses certain elements pertinent to education but

does not align closely with educational standards. It might mix educational content with

non-educational material, offering a superficial overview of potentially useful topics, or

presenting information in a disorganized manner and incoherent writing style.

- Award a third point if the extract is appropriate for educational use and introduces key

concepts relevant to school curricula. It is coherent though it may not be comprehensive

or could include some extraneous information. It may resemble an introductory section of

a textbook or a basic tutorial that is suitable for learning but has notable limitations like

treating concepts that are too complex for grade school students.

- Grant a fourth point if the extract highly relevant and beneficial for educational purposes

for a level not higher than grade school, exhibiting a clear and consistent writing style. It

could be similar to a chapter from a textbook or a tutorial, offering substantial educational

content, including exercises and solutions, with minimal irrelevant information, and the

concepts aren’t too advanced for grade school students. The content is coherent, focused,

and valuable for structured learning.

- Bestow a fifth point if the extract is outstanding in its educational value, perfectly suited for

teaching either at primary school or grade school. It follows detailed reasoning, the writing

style is easy to follow and offers profound and thorough insights into the subject matter,

devoid of any non-educational or complex content.

The extract: {example}.

After examining the extract:

- Briefly justify your total score, up to 100 words.

- Conclude with the score using the format: "Educational score: <total points>"

- DCLM: Inspired by DCLM, where authors trained a fastText classifier on high-quality data (OpenHermes 2.5 and r/ExplainLikeImFive) (Joulin et al., 2016; ML Foundations, 2024). We inspected the released classifier and datasets and concluded that it effectively targets instruction/Q&A documents. We therefore developed a prompt to fish for that type of content. We also used it to filter bait PDFs (score < 1).

DCLM prompt

Below is an extract from a PDF file. Evaluate whether the extract exhibits properties suitable for instruction-following or question-answering training data using the 6-point scoring system described below. Select the single score that best represents the extract's quality level:

**Score 0: Spam, Garbled, or Completely Unusable Content**

- Award 0 points for SEO spam content, promotional material with no educational value, completely garbled/corrupted text that is unreadable, random character sequences, or severely corrupted formatting that makes the content incomprehensible.

**Score 1: Simple Lists, Forms, or Minimal-Value Content**

- Award 1 point for content that has basic readable formatting but consists primarily of simple lists without context, forms, contact information, schedules, basic data tables without explanation, or other minimal-value structured content that lacks meaningful narrative or educational substance.

**Score 2: Cohesive Text Without Educational Value**

- Award 2 points if the extract contains cohesive, well-structured text that flows logically but lacks educational or instructional value. This includes meeting reports, business correspondence, letters, basic manual descriptions, administrative documents, or narrative content that doesn't teach or explain concepts.

**Score 3: Educational Content Without Q&A Structure**

- Award 3 points if the extract contains educational or informational content that could be useful for learning but doesn't follow a clear instructional format. This includes Wikipedia-style articles, research papers, academic content, encyclopedic entries, or explanatory text that presents information without explicit teaching structure.

**Score 4: Instructional Manuals and Structured Q&A**

- Award 4 points if the extract demonstrates clear instructional format with identifiable structure such as how-to guides, instruction manuals, structured question-answer pairs, problem-solution formats, or other organized pedagogical patterns. The content should be well-organized and follow recognizable educational conventions.

**Score 5: High-Quality Instructional Content with Explanations**

- Award 5 points if the extract exhibits exemplary instruction-response or question-answer properties with clear reasoning and detailed explanations. It should demonstrate thoughtful, step-by-step reasoning found in high-quality educational content like comprehensive tutorials, detailed explanations with context and reasoning, or expert-level instructional material that provides not just answers but explanatory reasoning and educational depth.

## Evaluation Process

The extract: {example}

After examining the extract:

- Briefly justify your total score, focusing on the content type and instructional/explanatory qualities, up to 100 words.

- Conclude with the score using the format: "Instruction/Q&A score: <total points>"

- EDU-V2: The original EDU prompt heavily targets grade-level documents, which can remove advanced textbooks or papers. Since our PDF corpus contains many of those, we wanted to see what happens if we target all educational documents, not just grade-level ones.

EDU-V2 prompt

Below is an extract from a PDF file. Evaluate whether the extract exhibits properties suitable for educational training data using the 6-point scoring system described below. Select the single score that best represents the extract's educational quality level:

**Score 0: No Educational Value**

- Award 0 points for content with zero educational merit including spam, promotional material, garbled text, random sequences, severely corrupted formatting, or content that provides no learning opportunities whatsoever.

**Score 1: Minimal Educational Content**

- Award 1 point for content with very limited educational value such as basic data listings, simple contact information, minimal factual statements without context, brief announcements, or content that presents isolated facts without meaningful educational framework.

**Score 2: Basic Informational Content**

- Award 2 points for content that provides basic information but lacks depth, context, or clear educational structure. This includes simple news items, basic product descriptions, brief summaries, casual observations, or informational content that states facts without explanation or educational development.

**Score 3: Moderate Educational Value**

- Award 3 points for content that offers solid educational information with some context and explanation. This includes informative articles with background information, basic explanatory content, introductory-level material, general knowledge content, or well-written informational pieces that provide context and some depth.

**Score 4: Strong Educational Content**

- Award 4 points for content with clear educational merit featuring detailed explanations, multiple perspectives, analytical depth, or comprehensive coverage of topics. This includes academic articles, detailed tutorials, in-depth analyses, research-based content, or material that demonstrates critical thinking and provides substantial learning value.

**Score 5: Exceptional Educational Value**

- Award 5 points for content with outstanding educational merit that demonstrates expert-level knowledge, sophisticated analysis, comprehensive understanding, and significant pedagogical value. This includes advanced academic research, expert commentary with deep insights, comprehensive educational material with multiple learning dimensions, or content that advances understanding through original thinking and thorough exploration.

## Evaluation Process

The extract: {example}

After examining the extract:

- Briefly justify your total score, focusing on the educational depth, context provided, and learning potential, up to 100 words.

- Conclude with the score using the format: "Educational value score: <total points>"

- OCR-Quality: As noted throughout this blog, PDF extraction is hard and artifacts are inevitable. We used a model to remove documents with obvious extraction issues.

OCR quality prompt

Below is an extract from a PDF file. Evaluate the quality of the document extraction using the 4-point string system described below. Select the single score that best represents the extraction quality level:

**Score 0: Garbage Text Present**

- Award 0 points if there are any garbage artifacts present in the text, regardless of how much legitimate content surrounds them. This includes OCR corruption like random character sequences (e.g., "7*/3./ +*/ 6- 4603"), unreadable symbol combinations, corrupted encoding artifacts, or any form of garbled text that renders portions of the document incomprehensible. Even if 90% of the text is perfectly readable, the presence of any garbage characters results in a score of 0.

**Score 1: Clear Formatting Issues**

- Award 1 point if there are no garbage characters but clear formatting problems are present. This includes broken mathematical equations or formulas that are unreadable, excessive or irregular spacing that disrupts readability, malformed tables or lists, severely corrupted line breaks, or other structural formatting issues that significantly impact the document's usability while keeping the text itself readable.

**Score 2: Minor Formatting Problems**

- Award 2 points if there are no garbage characters but minor formatting issues exist. This includes scattered extra spaces within words or sentences (e.g., "A t t h e S how"), inconsistent spacing, minor alignment issues, occasional broken line formatting, or small structural problems that don't severely impact readability but indicate imperfect extraction quality.

**Score 3: Clean Extraction**

- Award 3 points if there are no OCR garbage artifacts, no significant formatting issues, and the text extraction preserves the document's structure and readability effectively. The content should be clean, properly formatted, and easily readable with minimal to no extraction artifacts.

## Evaluation Process

The extract: {example}

After examining the extract:

- Briefly justify your score, focusing specifically on the presence of garbage text, formatting issues, and overall extraction quality, up to 100 words.

- Conclude with the score using the format: "Document extraction score: <total points>"

To test each prompt we labeled ~300k FinePDFs samples using the prompt with a teacher model (Qwen3‑235B‑A22B‑Instruct‑2507) (Qwen Team, 2025) and distilled the labels to a small bert model (ModernBERT-large) (Warner et al., 2024). By default we scored the first 2,048 tokens; if a document exceeded 10,000 characters, we also scored the last 2,048 tokens and took max(top, bottom).

To decide on a teacher we labeled 10k samples with Claude Sonnet‑4 (Anthropic, 2025) using the EDU and DCLM prompts, then scored the same set with candidate teachers and compared Mean Squared Error (MSE) to the Claude labels. We chose Qwen3‑235B‑A22B‑Instruct‑2507 because it gave the best overall trade‑off across EDU and DCLM, while also improving multilingual coverage and being very fast thanks to its MoE architecture (up to ~14 chunks/sec on a single H100).

| Model | MSE (DCLM) | MSE (EDU) |

|---|---|---|

| Qwen3-235B-A22B-Instruct-2507 | 0.42 | 0.40 |

| Qwen3-235B-A22B-Thinking-2507 | 0.32 | 0.81 |

| Qwen3-30B-A3B-Instruct-2507 | 0.55 | 0.36 |

| Qwen3-30B-A3B-Thinking-2507 | 0.29 | 0.93 |

| Qwen3-30B-A3B-Thinking-2507-FP8 | 1.20 | 0.89 |

| gemma-3-27b-it | 0.62 | 2.73 |

| Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct | 0.95 | 0.55 |

| Llama-4-Maverick-17B-128E-Instruct-FP8 | 0.84 | 0.71 |

| Llama-4-Scout-17B-16E-Instruct | 0.71 | 1.18 |

| Magistral-Small-2507 | 0.60 | 0.72 |

| Mistral-Nemo-Instruct-FP8-2407 | 0.82 | 5.12 |

| GLM-4.5-Air-FP8 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

With classifiers in hand we performed a quick sweep of possible thresholds (Figure 12). We were surprised to see the original EDU classifier perform so well compared to the others. While every classifier improved upon no filtering, both EDU‑V2 and OCR were nearly indistinguishable from no filtering at all. Interestingly, EDU‑V2 even degraded performance at higher score cutoffs. One possible explanation is that none of our evals is testing any sort of graduate/expert level knowledge. Even MMLU is at the grade level.

The only closer competitor to EDU was DCLM. The scores were strong but still below EDU at similar removal rates. However the classifier found use at the end; As we noted earlier, we designed the DCLM prompt to flag spammy PDFs by returning a score < 1. We use that variant to remove bait PDFs. We also evaluated the original fastText DCLM classifier; its performance was quite close, which aligns with our interpretation of what the DCLM model filter for: Q&A + Instructions.

To summarize, we used the DCLM classifier only as a light spam/bait filter for the English subset (removing score < 1), and we used the EDU to curate FinePDFs‑EDU by keeping the top 10% of documents per language. For FinePDFs‑EDU we extended the classifier to the top 70 languages using the same teacher model and mmBERT (Marone et al., 2025) as the student.

MinHash Deduplication and PII

Finally both FinePDFs as well as EDU subset underwent near-duplicate removal using MinHash signatures to estimate Jaccard similarity efficiently (Broder, 1997). We deduplicated globally per language as in (Penedo et al., 2025); the main change was increasing buckets (14 → 32) and hashes per bucket (8 → 10) because documents are longer and benefit from a larger signature (more hashes). We did not run a full ablation on these MinHash hyperparameters.

For PII removal, we have made no changes and removed IP addresses and email addresses from the dataset.

- Anthropic. (2025). Introducing Claude 4. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-4

- Broder, A. Z. (1997). On the resemblance and containment of documents. Proceedings of the Compression and Complexity of SEQUENCES 1997, 21–29. 10.1109/SEQUEN.1997.666900

- Gemma Team. (2025). Gemma 3 Technical Report. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.19786

- Joulin, A., Grave, E., Bojanowski, P., & Mikolov, T. (2016). Bag of Tricks for Efficient Text Classification. https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.01759

- Kargaran, A. H., Imani, A., Yvon, F., & Schütze, H. (2023). GlotLID: Language Identification for Low-Resource Languages. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.16248

- Marone, M., Weller, O., Fleshman, W., Yang, E., Lawrie, D., & Van Durme, B. (2025). mmBERT: A Modern Multilingual Encoder with Annealed Language Learning. https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.06888

- ML Foundations. (2024). DCLM-Baseline 1.0. https://huggingface.co/datasets/mlfoundations/dclm-baseline-1.0

- Penedo, G., Kydlícek, H., Ben Allal, L., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2024a). The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2406.17557. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17557

- Penedo, G., Kydlícek, H., Ben Allal, L., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2024b). The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2406.17557. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17557 back: 1, 2

- Penedo, G., Kydlícek, H., Ben Allal, L., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2025). FineWeb2: One Pipeline to Scale Them All – Adapting Pre-Training Data Processing to Every Language. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2506.20920. https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.20920 back: 1, 2, 3

- Poznanski, J., Rangapur, A., Borchardt, J., Dunkelberger, J., Huff, R., Lin, D., Wilhelm, C., Lo, K., Soldaini, L., & others. (2025). olmOCR: Unlocking Trillions of Tokens in PDFs with Vision Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.18443

- Qwen Team. (2025). Qwen3 Technical Report. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09388

- Warner, B., Chaffin, A., Clavié, B., Weller, O., Hallström, O., Taghadouini, S., Gallagher, A., Biswas, R., Ladhak, F., Aarsen, T., Cooper, N., Adams, G., Howard, J., & Poli, I. (2024). Smarter, Better, Faster, Longer: A Modern Bidirectional Encoder for Fast, Memory Efficient, and Long Context Finetuning and Inference. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.13663

Final dataset

That completes our processing pipeline. The result is two SoTA datasets: FinePDFs and FinePDFs-EDU. While we tried to preserve as many documents as possible, we still removed more than 66% of our initial dataset to create FinePDFs, and more than 96% to create FinePDFs-EDU. This massive reduction was mostly due to the deduplication steps and heavy model based filtering (for the EDU variant).

%%{init: {'sankey': {'linkColor': '#58B883', 'textColor': '#73a7f0', 'nodeAlignment': 'left', 'showValues': false, 'width': 1200, 'height': 520, 'useMaxWidth': true}}}%%

sankey-beta

Truncated<br/>(317.4M),URL dedup<br/>(303.2M),303233101

URL dedup<br/>(303.2M),Refetched<br/>(137.3M),137329078

Refetched<br/>(137.3M),Content dedup<br/>(1.29B),131013234

Non-trunc<br/>(1.33B),Content dedup<br/>(1.29B),1156317433

Content dedup<br/>(1.29B),OCR<br/>(368.8M),368786246

Content dedup<br/>(1.29B),Non-OCR<br/>(918.5M),918544421

OCR<br/>(368.8M),Non-failed<br/>(1.23B),318201145

Non-OCR<br/>(918.5M),Non-failed<br/>(1.23B),909768759

Non-failed<br/>(1.23B),English LID<br/>(582.7M),582674649

English LID<br/>(582.7M),Exact dedup<br/>(363.7M),363666269

Exact dedup<br/>(363.7M),Model filter<br/>(313.4M),313367202

Model filter<br/>(313.4M),Minhash<br/>(FinePDFs)<br/>(206.9M),206923789

Minhash<br/>(FinePDFs)<br/>(206.9M),FinePDFs-EDU<br/>(23.0M),23023372 SoTA dataset comparisons

As the final test for the quality of our pipeline and the resulting datasets, we compared them to current SoTA pretraining datasets: Nemotron-CC v2, FineWeb, FineWeb Edu, and FineWeb-Edu+DCLM (SmolLM3 mix) (Hugging Face TB Team, 2025).

Given our positive experience with mixing datasets (specifically FW-Edu+DCLM), we also experimented with combining PDFs and HTML corpora (FinePDFs+FW-Edu+DCLM) at various mixing ratios (0.1, 0.25, 0.5).

SoTA Dataset Comparisons

Rank across pretraining corpora (higher is better).

FinePDFs is not only on par with the dataset used to train Smolm3, but when properly mixed with FW-Edu+DCLM, it outperforms even the current SoTA (Nemotron-CC v2). FinePDFs-EDU is even more impressive: without any mixing, it already surpasses Nemotron-CC v2, and with mixing, it becomes the best performing dataset across all our ablations.

What’s inside the FinePDFs dataset?

Top URLs

While a deep dive into the dataset is impossible due to its sheer size, we can still get a sense of its composition by examining the top URLs.

To do so, we acquired the top 100 URLs by share for both English and non-English subsets. Both partitions are extremely long-tail, without a single dominating mega-source.

The English list is dominated by sites like GoDaddy (wsimg), S3, Google Cloud Storage, CloudFront, Squarespace, and Shopify. This is what PDF hosting looks like in practice—files live on CDNs, not on “official” domains. Aside from that, there are many government and legal sources (NRC, govinfo, state legislatures, Justia) and a solid block of science (arXiv, APS, Copernicus, MDPI).

High on the list is a site called equibase.com. What is it? It’s neither a PDF host, nor a government or legal source. Is it some mysterious site with PDFs containing all the knowledge of the world? No, it’s a website of hundreds of thousands of horse-racing records! We were quite surprised by this one, as we thought it would get filtered out by our MinHash deduplication. Clearly it didn’t, likely because of the constantly changing names and thorough descriptions of races.

The non‑English side mirrors the same pattern but through national portals: EUR‑Lex, BOE Spain, Czech (surprisingly this high up!) and Dutch university repositories, multiple Japanese ministries, and CNINFO for Chinese filings.

Length distribution

As we mentioned in the introduction, aside from achieving SoTA data quality, our secondary goal was to fill the gap in long-context documents, which are often missing but crucial for context extension during training.

Document length distribution

Violin plots compare log-scaled character lengths across four datasets. Median and interquartile ranges are highlighted.

The length distribution shows that we succeeded: FinePDFs is longer, with a ~5.3k character median (about 2× other corpora) and a much heavier tail (95th percentile ~68k vs ~11–13k elsewhere). This makes FinePDFs a great source for extending context during training.

FinePDFs beyond English

While the vast majority of ablations and decisions were based on the English part of the dataset (aside from LID), we continued monitoring our chosen canary languages from FineWeb2 to ensure we hadn’t caused any catastrophic regressions. At the end of the processing, we tested certain pipeline stages in more detail. Unlike our standard evaluation setup, we trained models for 99B tokens at the following stages: LID (no thresholding), LID (post thresholding), FinePDFs, and FinePDFs-Edu. We didn’t run FinePDFs-Edu for Arabic and Chinese, as we didn’t have enough tokens to train on.

Looking at the ablations, we were grateful to see no catastrophic drop in performance. Thresholding seems to have helped in some cases (Arabic, Russian) or had little to no effect (Chinese). We also compared results to our HTML-based dataset (FineWeb 2) and found FinePDFs to be better everywhere except in Russian.

- Hugging Face TB Team. (2025). SmolLM3 Technical Report. https://huggingface.co/HuggingFaceTB/SmolLM3-3B-Instruct

Appendix

Evaluation methodology

To validate the quality and our datasets, we use the same evaluation methodology established in our previous open-source releases. For each dataset, we trained 1.67B parameter models for 36B tokens using the Llama-3.2 tokenizer at a 4096 context length (extended because of PDFs length).

Once trained, models are evaluated across the following categories using lighteval:

- Reading Comprehension (RC): SQuAD v2 (Rajpurkar et al., 2018), DROP (Dua et al., 2019).

- Natural Language Understanding (NLU): HellaSwag (Zellers et al., 2019), Winogrande (Sakaguchi et al., 2021), Xstory-cloze (Lin et al., 2022).

- General Knowledge (GK): MMLU Redux (Gema et al., 2024), ARC-Easy (Clark et al., 2018).

- Reasoning (RES): OpenBookQA (Mihaylov et al., 2018), PiQA (Bisk et al., 2020), CommonsenseQA (Talmor et al., 2019).

- Mathematics (MATH): GSM8K (Cobbe et al., 2021).

- Table Understanding (TABLE): WikiTableQuestions (Pasupat & Liang, 2015), TrebQA (Yang & others, 2024).

Notably, we included Table Understanding (TABLE) benchmarks to specifically evaluate how filtering decisions impact the retention of structured information, which is a so often appear in PDF documents.

For multilingual evaluations (French, Chinese, Arabic, Russian), we have used the same tasks from FineTasks (Kydlícek et al., 2024).

For our primary metrics, we utilized token normalized probabilities of correct answers. This decision was heavily influenced by DataDecide (Magnusson et al., 2025), which demonstrated that log-probabilities (and inherently probabilities) offer superior stability and are better predictors of future performance at scale compared to traditional accuracy metrics. Furthermore, they offer significant computational efficiency during the evaluation phase.

To aggregate results, we employed rank averages across task categories instead of arithmetic means. Mostly to account for varying scales and distributions inherent to log-probabilities across different tasks, ensuring that no single task disproportionately biases the overall score. The results are first rank averaged per category and then the final score is computed as average over the categories.

Generative Evaluations

A big concern we have with pretraining evaluation is whether our current evaluation pipelines effectively capture real-world utility or merely optimize for narrow, artificial metrics. This concern arises because both log-probabilities and MCQ accuracy often don’t evaluate the model the same way it’s used: prompted to generate open-ended answers along whatever trajectory they require.

In practice, models are rarely constrained to follow predefined trajectories or rank answers against artificial distractors. Consider a reasoning model trained from scratch; it might perform poorly on traditional evaluations because its natural output for a simple question like “Who is the president of the USA?” might be:

Okay, let’s think about this… the current president is Donald Trump.

…rather than the expected answer “Donald Trump”.

Surprisingly, purely generative evaluations, are almost exlcusively used only during post-training evaluation. We believe the primal reason is the belief (we are guilty of such thoughts ourselves) that pre-trained models wouldn’t follow the expected format well, are too “dumb” to be able to generate correct answer and don’t know when to stop.

While these challenges are real—as we observed when introducing generative evaluations in FineTasks (Kydlícek et al., 2024) (F1 scores struggle with yappy model outputs)—there is a solution: LLM-as-a-Judge, as demonstrated in recent work (Nikhil Chandak, 2025).

We therefore adapted our generative and MCQ tasks into free-form generative tasks, filtering for samples with a single clear answer. We evaluated these using an LLM-as-a-Judge against ground truth references. Not all tasks are amenable to this conversion (e.g., HellaSwag relies on knowledge of other options), so we only used the following:

- CommonsenseQA

- MMLU Redux

- ARC-Easy

- GSM8K

- SQuAD

- TrebQA

We re-evaluated all the datasets we compared against FinePDFs as well as FinePDFs itself using this new methodology. As for LLM we used the most Claude-like model we knew.

LLM-as-a-Judge Prompt

<System>

Your task is to judge whether the given response to a question matches a given ground truth answer or not. You are provided with a question, a ground truth response, and the response you need to judge.

Your job is to ONLY check whether the given response matches the ground truth answer or not in the context of the question. You DO NOT NEED to assess the correctness of the response.

Possible judgments:

* 0: The response does not match the ground-truth answer

* 1: The response matches the ground-truth answer

Your output must:

1. Provide a brief explanation first.

2. End with the line: `ANSWER: 0` or `ANSWER: 1`

Example 1:

Question: `What is the capital of France?`

Ground truth: `Paris`

Response: `The capital of France is Paris, which is located in the north-central part of the country.`

Output:

\`\`\`

The response correctly states that Paris is the capital of France.

ANSWER: 1

\`\`\`

Example 2:

Question: `How many gold medals did the USA win in the 2020 Olympics?`

Ground truth: `39`

Response: `The United States performed exceptionally well in the Tokyo Olympics, winning numerous medals across various sports categories.`

Output:

\`\`\`

The response does not include the specific number of gold medals (39).

ANSWER: 0

</System>

<User>

Question: \`\`\`{question}\`\`\`

Ground truth: \`\`\`{ground_truth}\`\`\`

Response: \`\`\`{response_text}\`\`\`

</User>

To our surprise, not only did we achieve non-zero scores across all tasks, but the results exhibited remarkable monotonicity—with scores steadily increasing alongside training steps.

Furthermore, we investigated the correlation between our primary metric (probability of correct answer) and the judge-based assessment using the Decision Accuracy as defined in DataDecide (Magnusson et al., 2025).

| Task | Metric | Decision Accuracy vs Judge |

|---|---|---|

| ARC | Log-probs | 0.908 |

| MMLU Redux | Log-probs | 0.920 |

| CommonSenseQA | Log-probs | 0.869 |

While it shows that there is clearly great correlation and one can fairly expect the same results from both metrics, going forward we believe the purely generative evals should be used for pretraining evaluation not matter the stage. It not only models the real-world utility better, but also can be consistently used across all the stages.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following individuals and teams for their invaluable contributions to this work:

- Hugo Larcher and Mathieu Morlon: For maintaining the HF cluster and providing expert assistance with infrastructure issues.

- CommonCrawl Team: For maintaining the CommonCrawl dataset and providing detailed answers to our data-related inquiries.

- Docling Team: For helping us adapt the Docling library to meet our specific processing requirements.

- Thibaud Frere: For creating the beautiful research article template.

- Bisk, Y., Zellers, R., Bras, R. L., Gao, J., & Choi, Y. (2020). PIQA: Reasoning about Physical Commonsense in Natural Language. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.11641

- Clark, P., Cowhey, I., Etzioni, O., Khot, T., Sabharwal, A., Schoenick, C., & Tafjord, O. (2018). Think you have Solved Question Answering? Try ARC, the AI2 Reasoning Challenge. arXiv Preprint arXiv:1803.05457. https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.05457

- Cobbe, K., Kosaraju, V., Bavarian, M., Chen, M., Jun, H., Kaiser, L., Plappert, M., Tworek, J., Hilton, J., Nakano, R., Hesse, C., & Schulman, J. (2021). Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems. https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.14168

- Dua, D., Wang, Y., Dasigi, P., Stanovsky, G., Singh, S., & Gardner, M. (2019). DROP: A Reading Comprehension Benchmark Requiring Discrete Reasoning Over Paragraphs. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), 2368–2378. https://aclanthology.org/N19-1246/

- Gema, A. P., Ong, J. L., Hong, G., Devoto, A., Mancino, A. C. M., Saxena, R., He, X., Zhao, Y., Du, X., Madani, M. R. G., & others. (2024). Are We Done with MMLU? arXiv Preprint arXiv:2406.04127. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04127

- Kydlícek, H., Penedo, G., Fourier, C., Habib, N., & Wolf, T. (2024). FineTasks: Finding signal in a haystack of 200+ multilingual tasks. Hugging Face. https://huggingface.co/spaces/HuggingFaceFW/blogpost-fine-tasks back: 1, 2

- Lin, X. V., Mihaylov, T., Artetxe, M., Wang, T., Chen, S., Simig, D., Ott, M., Goyal, N., Bhosale, S., Du, J., Pasunuru, R., Shleifer, S., Koura, P. S., Chaudhary, V., O’Horo, B., Wang, J., Zettlemoyer, L., Kozareva, Z., Diab, M., … Li, X. (2022). Few-shot Learning with Multilingual Generative Language Models. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.10668

- Magnusson, I., Tai, N., Dodge, J., & others. (2025). DataDecide: How to Predict Best Pretraining Data with Small Experiments. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.11393 back: 1, 2

- Mihaylov, T., Clark, P., Khot, T., & Sabharwal, A. (2018). Can a Suit of Armor Conduct Electricity? A New Dataset for Open Book Question Answering. Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.02789

- Nikhil Chandak. (2025). Answer Matching Outperforms Multiple Choice for Language Model Evaluation. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.02856

- Pasupat, P., & Liang, P. (2015). Compositional Semantic Parsing on Semi-Structured Tables. Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL). https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.00305

- Rajpurkar, P., Jia, R., & Liang, P. (2018). Know What You Don’t Know: Unanswerable Questions for SQuAD. Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL). https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.03822

- Sakaguchi, K., Bras, R. L., Bhagavatula, C., & Choi, Y. (2021). Winogrande: An Adversarial Winograd Schema Challenge at Scale. Communications of the ACM, 64(9), 99–106. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.10641

- Talmor, A., Herzig, J., Lourie, N., & Berant, J. (2019). CommonsenseQA: A Question Answering Challenge Targeting Commonsense Knowledge. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, 4149–4158. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.00937

- Yang, Z., & others. (2024). TReB: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Table Reasoning. arXiv Preprint. https://github.com/JT-LM/jiutian-treb

- Zellers, R., Holtzman, A., Bisk, Y., Farhadi, A., & Choi, Y. (2019). HellaSwag: Can a Machine Really Finish Your Sentence? Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4791–4800. https://aclanthology.org/P19-1472/